Health inequalities

What are health inequalities and how are they measured?

Health inequalities are differences between groups of people due to social, geographical, biological or other factors. These differences have a huge impact, because they result in people who are worst off experiencing poorer health and shorter lives.

Health inequalities are differences between groups of people due to social, geographical, biological or other factors. These differences have a huge impact, because they result in people who are worst off experiencing poorer health and shorter lives.

One of the main methods of measuring health inequalities is though measuring health outcomes for each deprivation quintile. More information is available in the deprivation and poverty section. This helps commissioners and health professionals understand the direction and strength of the relationship between deprivation and health outcomes. Typically, outcomes between those living in the most deprived areas are compared with those in the least deprived. This allows the inequality gap to be monitored over time to identify if progress is being made to narrow inequalities within the city. The inequality gap can be expressed as the percentage difference or the factor difference in health related indicators between those living in the most deprived and the least deprived areas.

Life expectancy, healthy life expectancy and mortality

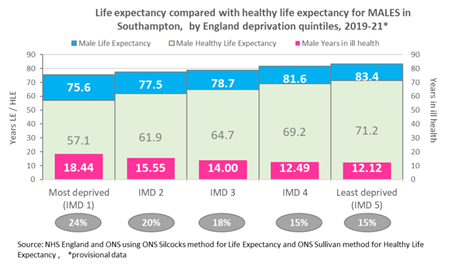

Life expectancy in England has generally increased in recent decades, however, life expectancy is not uniform across England and inequalities exist, with those in the most deprived areas living shorter lives than those in the least deprived areas. In Southampton, when looking at the local deprivation quintiles for the 2019-21 period, males living in the most deprived areas of the city on average live 6.3 years less than those living in the least deprived areas and females 4.3 years less, with no evidence this inequality gap in life expectancy narrowing over time.

Life expectancy in England has generally increased in recent decades, however, life expectancy is not uniform across England and inequalities exist, with those in the most deprived areas living shorter lives than those in the least deprived areas. In Southampton, when looking at the local deprivation quintiles for the 2019-21 period, males living in the most deprived areas of the city on average live 6.3 years less than those living in the least deprived areas and females 4.3 years less, with no evidence this inequality gap in life expectancy narrowing over time.

When investigating inequalities in mortality there is a greater focus on premature mortality (those aged under 75 years). All cause premature mortality is significantly higher in the most deprived areas of the city compared to the least deprived, with the rate almost twice as high for those living in the most deprived areas of the city. Those living in the most deprived areas of the city also experience significantly higher rates of premature mortality from circulatory diseases and cancer, with the mortality rate from circulatory disease 1.89 times higher and from cancer 1.54 times higher in the most deprived areas of the city compared to the least deprived.

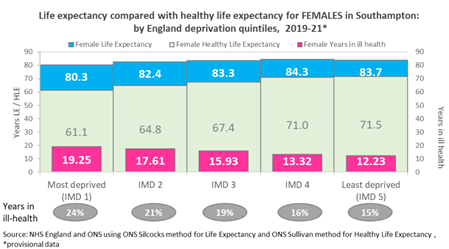

Females in the city may live longer than males but they live in poorer health for longer which ever deprivation quintile they live in.

Females in the city may live longer than males but they live in poorer health for longer which ever deprivation quintile they live in.

Looking at life expectancy versus healthy life expectancy, in the most deprived 20% England quintiles (used by Core20+5 analysis), males live on average for 18.4 years in ill health however females live for 19.2 years in ill health. Both males and females in the most deprived quintile live a quarter (24%) of their shorter lives in ill health. Males and females in the least deprived quintile live a seventh (15%) of their lives in ill health.

More information can be found on our life expectancy page.

Physical ill health and wellbeing

Not only do those living in the most deprived areas in England live shorter lives, but they also experience worse physical health than those living in the least deprived areas. Within England, people living in the most deprived areas on average develop long-term conditions 10 to 15 years earlier than the general population. More information can be found in the blog on closing the gap on health inequality, from NHS England.

In the most deprived areas of Southampton compared to the least:

- The prevalence of COPD is 2.1 times higher

- Emergency admissions for COPD are 1.5 times higher

- Asthma prevalence is 1.2 times higher

- Emergency admissions for asthma are 4.2 times higher

- The prevalence of Ischaemic Heart Disease is 1.51 times higher

- Hypertension prevalence is 1.20 times higher

- Diabetes prevalence is 1.64 times higher

- Coronary Heart Disease prevalence is 3.9 times higher

- Cardiovascular Disease prevalence is 1.8 higher

- Prevalence of Multiple (3 or more) Long Term Conditions is 1.42 times higher

Mental ill health and wellbeing

One in four adults and one in 10 children experience mental illness at any one time, and many more of us know and care for people who do. Improved mental health and wellbeing is associated with a range of better outcomes for people of all ages and backgrounds. Mental health and wellbeing are also important influences on health behaviours as well as being a health outcome in their own right (NHS England – mental health).

Mental illnesses are unevenly distributed across society, with disproportionate impacts on those living in the most deprived areas more information can be found in the mental health and wellbeing section.

In Southampton, the prevalence of mental illnesses such as depression (1.78 times higher) and severe mental illnesses such as Schizophrenia (2.77 times higher) and Bipolar Disorder (2.77 times higher) are significantly higher in the most deprived areas of the city compared to the least deprived areas.

Not only do inequalities exist in the prevalence of mental illnesses, but in outcomes. Self-harm is considered an outcome of mental illness, as a person is more at risk of self-harm if they have a mental illness, with some self-harm events severe enough to warrant hospital admission. In Southampton, in 2015-17, the emergency admission rate for self-harm is 3.49 times higher in the most deprived areas of the city compared to the least deprived.

Healthy behaviours

Inequalities also exist in the prevalence of healthy behaviours that cause ill health. Smoking, inactivity and excessive drinking are some of the leading causes of preventable ill health and premature mortality in the UK.

Smoking is a major risk factor for diseases such as but not limited to lung cancer, COPD, and heart disease. In Southampton, the prevalence of smoking among registered patients is 2.3 times higher for those living in the most deprived areas of the city compared to the least deprived.

People who are physically active have a 20-35% lower risk of cardiovascular diseases compared to those who are inactive. This protective effect is significantly higher than that reported by previous questionnaire-based studies. These estimated the protective effect of physical exercise against cardiovascular disease, for those who are more versus less active, to be about 20%-25% for total physical activity, 20%-25% for moderate-intensity physical activity, and 30%-35% for vigorous-intensity physical activity. Big Data Institute.

An active lifestyle is also associated with a lower risk of diabetes, obesity, osteoporosis, various types of cancer and mental health conditions. Inactivity is 2.63 times higher among those living in the most deprived areas of the city compared to the least deprived (2018 City Survey). For more information, see the resources section below.

Alcohol use is estimated to cost the NHS about £3.5 billion per year and society as a whole £21 billion annually. Alcohol-specific admissions describe hospital admissions for conditions that are wholly attributed to alcohol. See the resources section below for more information. Alcohol-specific hospital admissions are 3.39 times higher in the most deprived areas of the city compared to the least. The inequality gap between the most and least deprived areas appears to have decreased; however, this reduction is due to an increase in the admission rate for those living in the least deprived areas.

Healthy start and children

Supporting good maternal health is important for the safe delivery and good birth weight to give babies the best start in life, as what happens in pregnancy and early childhood impacts on physical and emotional health all the way through to adulthood.

Breast milk provides ideal nutrition for infants in the first stages of life and helps to reduce infections in infants. However, the proportion of mother’s breastfeeding is 1.38 times lower for those living in the most deprived areas of the city when compared with the least deprived.

It is estimated that smoking during pregnancy can cause up to 2,200 premature births, 5,000 miscarriages and 300 perinatal deaths in the UK every year. Smoking during pregnancy can also increase the risk of complications in pregnancy and of the child developing a number of conditions later in life such as, but not limited to:

- Premature birth

- Low birth weight

- Respiratory conditions

- Diabetes

- Obesity

- Problems of the ear, nose and throat

Therefore, reducing the number of mothers smoking during pregnancy is vital to maternal health and children’s development. Mothers from more deprived areas are more likely to smoke; this is evidenced within Southampton, as the proportion of mothers smoking at midwifery booking is 16.9 times higher for those living in the most deprived areas compared to those living in the least deprived. For more information, see the resources section below.

The rise in obesity among children is a key public health concern, as this increases the risk of obesity persisting into adulthood and developing obesity related ill health. There is a strong link with childhood obesity and deprivation, the prevalence of obesity is 1.6 times higher for Year R children and 1.9 times higher for Year 6 children living in the most deprived areas of the city compared to the least deprived. For more information, see children and young people section.

Wider determinants

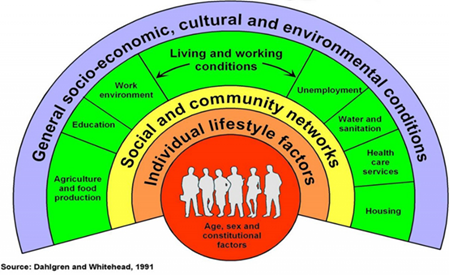

Wider determinants describe a diverse range of social, economic and environmental factors, which impact people’s health and daily living. The Marmot Review (2010) emphasised the strong and continuous link between inequalities in wider determinants and disparities in health outcomes. Variation in the experience of wider determinants is considered to be the fundamental cause of health outcomes. Therefore, addressing the wider determinants of health is important in reducing health inequalities within the city.

Wider determinants describe a diverse range of social, economic and environmental factors, which impact people’s health and daily living. The Marmot Review (2010) emphasised the strong and continuous link between inequalities in wider determinants and disparities in health outcomes. Variation in the experience of wider determinants is considered to be the fundamental cause of health outcomes. Therefore, addressing the wider determinants of health is important in reducing health inequalities within the city.

Children’s early experiences have a significant impact on their development, educational attainment and future life chances. Within Southampton, the majority of looked after children come from the most deprived areas, with the rate 3.95 times higher than those living in the least deprived areas of the city. Children living in the most deprived areas of the city also have lower educational attainment and are more likely to live in low-income families.

Many physical and mental health outcomes improve incrementally as income rises, as financial resources determine the extent to which a person can both invest in goods and services that improve health and purchase goods and services, which are bad for health. Those living in the most deprived areas of the city are more likely to be unemployed, with unemployment 5.33 times higher compared to the least deprived parts of the city.

Crime can affect physical and mental health in many ways. Violence against the person is the most direct link between crime and health. However, the psychological effects of experiencing crime can have far-reaching consequences, such as reducing health promoting behaviours like physical activity and social interaction. Locally, recorded crime is 3.02 times higher in the most deprived areas of the city when compared with the least deprived. For more information on crime, see the Community Safety section.

Resources

Neighbourhood Analysis of Need

This work highlights need and inequalities among Southampton neighbourhoods across a number of key theme areas, including demography, children’s social care, youth crime and violence, healthy start, child health and need, adult health and need, education and poverty and deprivation.

Analysis of Inequalities in Southampton

A slide set of health inequalities across Southampton.

Fair Society, Healthy Lives (The Marmot Review)

In November 2008, Professor Sir Michael Marmot was asked by the then Secretary of State for Health to chair an independent review to propose the most effective evidence-based strategies for reducing health inequalities in England from 2010.

OHID - Inclusion Health Groups in Hampshire and the Isle of Wight ICS: An overview of available data and published evidence

This data pack is provides a one-off summary of available data and evidence for inclusion health groups in the South East at an ICB level. It presents an initial overview to support systems to understand need in their area and provide a resource including data and summaries that can be taken out and used as required, as well as be further developed by local Systems. For each inclusion health group, the key messages for systems are presented, followed by an overview of health issues and available data.

OHID - Health disparities and health inequalities: applying All Our Health

This guide is part of All Our Health, a resource that helps health and care professionals and the wider workforce prevent ill health and promote wellbeing as part of their everyday practice. All Our Health content on inclusion health, community-centred practice and improving the wider determinants of health may be of particular interest in connection with this topic.

OHID - Public Health Outcomes Framework

The Public Health Outcomes Framework sets out a vision for public health, that is to improve and protect the nation's health, and improve the health of the poorest fastest

OHID Fingertips – Local Alcohol Profiles for England

The indicators contained within this profile were selected following consultation with stakeholders and a review of the availability of routine data. The Local Alcohol Profiles for England (LAPE) are part of a series of products by Public Health England that provide local data alongside national comparisons to support local health improvement.

Last updated: 28 September 2023